Biology Seminar

*Cancelled* Gregory Seminar

*Cancelled* Gregory Seminar

"Cellular Respiration: A Teaching Demonstration"

Dr. Megan DeWhatley

Bio:

Dr. Megan DeWhatley is an associate teaching professor of biological aciences at St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas. She has a Ph.D. in biology from the University of Louisville and more than seven years of teaching experience in higher education, primarily in introductory biology lectures and labs. At her current institution, DeWhatley is the coordinator of the General Biology I lecture courses, the General Biology II lecture courses and the General Biology I Labs. In her free time, she enjoys hiking and poking around in creeks.

Abstract:

In this seminar, DeWhatley will summarize her teaching experience and give a teaching demonstration on the activities of every student’s favorite organelle: the powerhouse of the cell. During the teaching demonstration, DeWhatley will display an instructional style that incorporates active learning and lecture to introduce the topic of cellular respiration for an audience of undergraduate biology majors in an introductory biology course.

"Cellular Respiration: A Teaching Demonstration"

Dr. Megan DeWhatley

Bio:

Dr. Megan DeWhatley is an associate teaching professor of biological aciences at St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas. She has a Ph.D. in biology from the University of Louisville and more than seven years of teaching experience in higher education, primarily in introductory biology lectures and labs. At her current institution, DeWhatley is the coordinator of the General Biology I lecture courses, the General Biology II lecture courses and the General Biology I Labs. In her free time, she enjoys hiking and poking around in creeks.

Abstract:

In this seminar, DeWhatley will summarize her teaching experience and give a teaching demonstration on the activities of every student’s favorite organelle: the powerhouse of the cell. During the teaching demonstration, DeWhatley will display an instructional style that incorporates active learning and lecture to introduce the topic of cellular respiration for an audience of undergraduate biology majors in an introductory biology course.

"Cellular Respiration: A Teaching Demonstration"

Dr. Megan DeWhatley

Bio:

Dr. Megan DeWhatley is an associate teaching professor of biological aciences at St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas. She has a Ph.D. in biology from the University of Louisville and more than seven years of teaching experience in higher education, primarily in introductory biology lectures and labs. At her current institution, DeWhatley is the coordinator of the General Biology I lecture courses, the General Biology II lecture courses and the General Biology I Labs. In her free time, she enjoys hiking and poking around in creeks.

Abstract:

In this seminar, DeWhatley will summarize her teaching experience and give a teaching demonstration on the activities of every student’s favorite organelle: the powerhouse of the cell. During the teaching demonstration, DeWhatley will display an instructional style that incorporates active learning and lecture to introduce the topic of cellular respiration for an audience of undergraduate biology majors in an introductory biology course.

"How about a light snack? - Photosynthesis Teaching Demonstration"

Dr. Mary Foley

Dr. Mary Foley

Bio:

Mary Foley is a postdoctoral researcher in biology education at Middle Tennessee State University. She received her undergraduate degree in biology from the University of Kentucky. She earned a master’s degree in microbial biology from Rutgers University, where she studied the function of the YlaN protein in Staphylococcus aureus. She earned her Ph.D. from the University of Kentucky, where she performed microbiome research under David Weisrock and Luke Moe.

During that time, she also began her journey in biology education research under Jennifer Osterhage, which motivated her to pursue a postdoc in biology education. Over her academic career, she has taught a range of undergraduate biology courses, including introductory biology, microbiology and research-based lab courses. She has recent experience teaching a large introductory biology lecture. Her teaching focuses on helping students build confidence and a sense of belonging in biology through active engagement with the material, by connecting the course material to real-world issues and by practicing effective science communication.

Abstract:

My research journey reflects a sustained interest in biology, spanning biological systems and how undergraduate biology students learn science. My training as a bench biologist, conducting molecular microbiology and microbiome research, provided extensive experience in experimental design and data analysis, as well as firsthand exposure to the nature of scientific inquiry. Through teaching undergraduate research courses as a graduate student, I became increasingly interested in the distinction between the skills needed to succeed in a science class and those required to succeed in science more broadly. This realization led me to transition into biology education research, where I currently examine how undergraduate research experiences and science communication activities influence students’ motivation and science identity.

My research background directly informs my teaching. Drawing on both my disciplinary and educational research, I design courses that emphasize skills such as data interpretation, science communication and critical thinking alongside core biological concepts, while promoting curiosity, resilience, and reflection, skills I believe are necessary for both success in science careers and improving society through science. My teaching demonstration reflects this approach through learning goals that include tracing the transformation of energy and matter through photosynthesis, explaining how pigment structure enables light capture, evaluating the biological origin of plant biomass in the context of climate change mitigation and practicing effective dialogue around climate change.

"How about a light snack? - Photosynthesis Teaching Demonstration"

Dr. Mary Foley

Dr. Mary Foley

Bio:

Mary Foley is a postdoctoral researcher in biology education at Middle Tennessee State University. She received her undergraduate degree in biology from the University of Kentucky. She earned a master’s degree in microbial biology from Rutgers University, where she studied the function of the YlaN protein in Staphylococcus aureus. She earned her Ph.D. from the University of Kentucky, where she performed microbiome research under David Weisrock and Luke Moe.

During that time, she also began her journey in biology education research under Jennifer Osterhage, which motivated her to pursue a postdoc in biology education. Over her academic career, she has taught a range of undergraduate biology courses, including introductory biology, microbiology and research-based lab courses. She has recent experience teaching a large introductory biology lecture. Her teaching focuses on helping students build confidence and a sense of belonging in biology through active engagement with the material, by connecting the course material to real-world issues and by practicing effective science communication.

Abstract:

My research journey reflects a sustained interest in biology, spanning biological systems and how undergraduate biology students learn science. My training as a bench biologist, conducting molecular microbiology and microbiome research, provided extensive experience in experimental design and data analysis, as well as firsthand exposure to the nature of scientific inquiry. Through teaching undergraduate research courses as a graduate student, I became increasingly interested in the distinction between the skills needed to succeed in a science class and those required to succeed in science more broadly. This realization led me to transition into biology education research, where I currently examine how undergraduate research experiences and science communication activities influence students’ motivation and science identity.

My research background directly informs my teaching. Drawing on both my disciplinary and educational research, I design courses that emphasize skills such as data interpretation, science communication and critical thinking alongside core biological concepts, while promoting curiosity, resilience, and reflection, skills I believe are necessary for both success in science careers and improving society through science. My teaching demonstration reflects this approach through learning goals that include tracing the transformation of energy and matter through photosynthesis, explaining how pigment structure enables light capture, evaluating the biological origin of plant biomass in the context of climate change mitigation and practicing effective dialogue around climate change.

"How about a light snack? - Photosynthesis Teaching Demonstration"

Dr. Mary Foley

Dr. Mary Foley

Bio:

Mary Foley is a postdoctoral researcher in biology education at Middle Tennessee State University. She received her undergraduate degree in biology from the University of Kentucky. She earned a master’s degree in microbial biology from Rutgers University, where she studied the function of the YlaN protein in Staphylococcus aureus. She earned her Ph.D. from the University of Kentucky, where she performed microbiome research under David Weisrock and Luke Moe.

During that time, she also began her journey in biology education research under Jennifer Osterhage, which motivated her to pursue a postdoc in biology education. Over her academic career, she has taught a range of undergraduate biology courses, including introductory biology, microbiology and research-based lab courses. She has recent experience teaching a large introductory biology lecture. Her teaching focuses on helping students build confidence and a sense of belonging in biology through active engagement with the material, by connecting the course material to real-world issues and by practicing effective science communication.

Abstract:

My research journey reflects a sustained interest in biology, spanning biological systems and how undergraduate biology students learn science. My training as a bench biologist, conducting molecular microbiology and microbiome research, provided extensive experience in experimental design and data analysis, as well as firsthand exposure to the nature of scientific inquiry. Through teaching undergraduate research courses as a graduate student, I became increasingly interested in the distinction between the skills needed to succeed in a science class and those required to succeed in science more broadly. This realization led me to transition into biology education research, where I currently examine how undergraduate research experiences and science communication activities influence students’ motivation and science identity.

My research background directly informs my teaching. Drawing on both my disciplinary and educational research, I design courses that emphasize skills such as data interpretation, science communication and critical thinking alongside core biological concepts, while promoting curiosity, resilience, and reflection, skills I believe are necessary for both success in science careers and improving society through science. My teaching demonstration reflects this approach through learning goals that include tracing the transformation of energy and matter through photosynthesis, explaining how pigment structure enables light capture, evaluating the biological origin of plant biomass in the context of climate change mitigation and practicing effective dialogue around climate change.

"Severe Alteration of the Cell Surface in Acinetobacter baumannii to Unravel Peptidoglycan Physiology"

Dr. Brent Simpson

Bio:

Brent Simpson trained at the Ohio State University, where he received his Ph.D. working in the laboratory of Natacha Ruiz. During his Ph.D., he studied how Gram-negative bacteria build the outer membrane and published three lead-author papers exploring the mechanism of LPS transport. He also received awards for both excellence in teaching and a distinguished dissertation during his graduate work. Brent then moved to the University of Georgia to work with Stephen Trent.

He began working on why LPS is essential in most Gram-negative bacteria using a rare model organism that is able to survive with complete absence of its version of LPS that is missing O-antigen and called LOS. He performed the first transposon-sequencing in a Gram-negative organism completely missing LPS or LOS. This experiment revealed new details about multiple aspects of peptidoglycan physiology in the Gram-negative pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii.

He has published four papers in mBio, PNAS and Journal of Bacteriology following up on peptidoglycan physiology. In addition, he was awarded an NIH F32 Kirschstein fellowship and the UGA Postdoctoral Research Award for his research contributions. He plans to leverage his data set to learn more about cell physiology of Acinetobacter and other Gram negatives with the hope of developing strategies to overcome multi-drug resistant infections. Brent is passionate about microbial physiology, mentoring and teaching students, and his three cats.

Abstract:

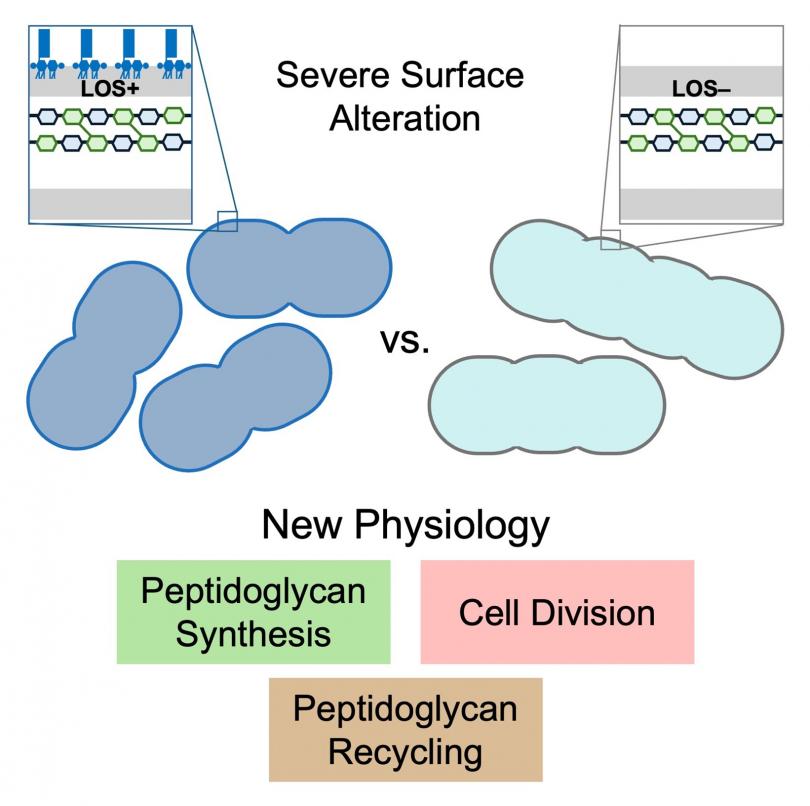

Bacteria have evolved different cell envelope compositions that provide them specific advantages in their natural environments or as human pathogens. Gram-negative bacteria have a three-layered cell envelope with an inner membrane, peptidoglycan, and outer membrane.

The outer membrane has asymmetric organization of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or lipooligosaccharide (LOS) only on the cell surface. LPS and LOS differ only in the presence (LPS) or absence (LOS) of an O-antigen. LPS/LOS is essential in most Gram negatives serving both as a permeability barrier and providing rigidity to the cell surface. Peptidoglycan is a mesh of long polysaccharide chains crosslinked with short peptides, that also provides rigidity to the cell. The outer membrane and peptidoglycan are critical structures of the cell that if targeted by antimicrobial therapy can cause bacterial clearance.

The high-priority Gram-negative pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii normally produces an LOS-containing outer membrane, but it is remarkably able to survive even with complete loss of LOS. We have used the comparison of A. baumannii with and without LOS as a critical tool to understand how it builds its cell envelope. A transposon sequencing approach in A. baumannii completely missing LOS unveiled new aspects of peptidoglycan synthesis, recycling, and degradation during cell division. Understanding the biogenesis of the outer membrane and peptidoglycan has broad implications in bacterial pathogenesis, antimicrobial resistance and the development of new therapeutic strategies.